Helen Frankenthaler, Matisse Table, 1972

Sala 1

«L’ho realizzato a Londra quando ho lavorato nello studio dello scultore Anthony Caro un’estate [nel 1972] e ho eseguito dieci sculture in metallo… qualche anno dopo lui è venuto nel mio studio a New York e ha dipinto».

—Trascrizione della conferenza a Palm Springs, 1996.

«Stavo fissando il cosiddetto Ananas di Matisse del ’48 [riprodotto su un grande poster nello studio di Caro]…, e pensavo: potrebbe essere tradotto in qualche modo in una scultura?».

—Trascizione della conferenza all’AIC.

“I made this in London when I worked at the sculptor Anthony Caro’s studio one summer [in 1972] and made ten metal sculptures . . . a few years later, he came to my studio in New York and painted.”

—Palm Springs lecture transcript, 1996.

“I had been staring at a Matisse [painting] called Pineapple from ’48 [reproduced on a large poster in Caro’s studio] . . ., and thought, could that in any way be translated into a sculpture?”

—AIC lecture transcript, 1991.

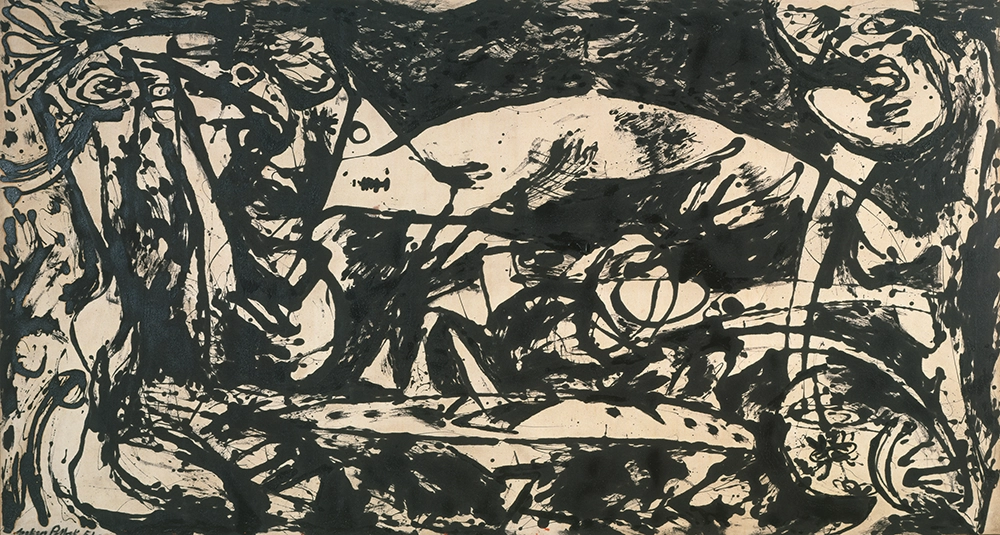

Jackson Pollock, Number 14, 1951

Sala 2

«[Numero 14 di Pollock] era più di semplice disegno, tessitura, intreccio, gocciolamento di un bastoncino immerso nello smalto, più di semplice ritmo. Sembrava avere una complessità e un ordine tali da suscitare, in quel momento, una mia reazione. Qualcosa di più… barocco, più disegnato e con alcuni elementi di realismo astratto o di Surrealismo, o un loro riflesso… È un dipinto totalmente astratto, ma per me aveva in più questa qualità».

—Intervista di Barbara Rose, 1968.

“[Pollock’s Number 14] was more than just the drawing, webbing, weaving, dripping of a stick held in enamel, more than just the rhythm. It seemed to have much more complication and order of a kind that at the time I responded to. Something . . . more baroque, more drawn and with some elements of realism abstracted or Surrealism or a hint of it . . . It is a totally abstract picture, but it had that additional quality . . . for me.”

—Interview by Barbara Rose, 1968

Helen Frankenthaler, Open Wall, 1953

Sala 2

«[Il dipinto è iniziato come] un esperimento per creare una sorta di senso di spazio e di confine… In definitiva l’essenza del dipinto, ciò che suscita una reazione, ha ben poco a che fare con il soggetto in sé, ma piuttosto con l’interazione degli spazi e la giustapposizione delle forme».

—Intervista di Julia Brown, After Mountains and Sea, catalogo della mostra, 1998.

“[The painting began as] an experiment to create some kind of sense of space and boundary. . . In the end, a spine of the painting, what makes one respond, has very little to do with the subject matter per se but rather the interplay of spaces and juxtapositions of forms.”

—Interview by Julia Brown, After Mountains and Sea exh. cat., 1998.

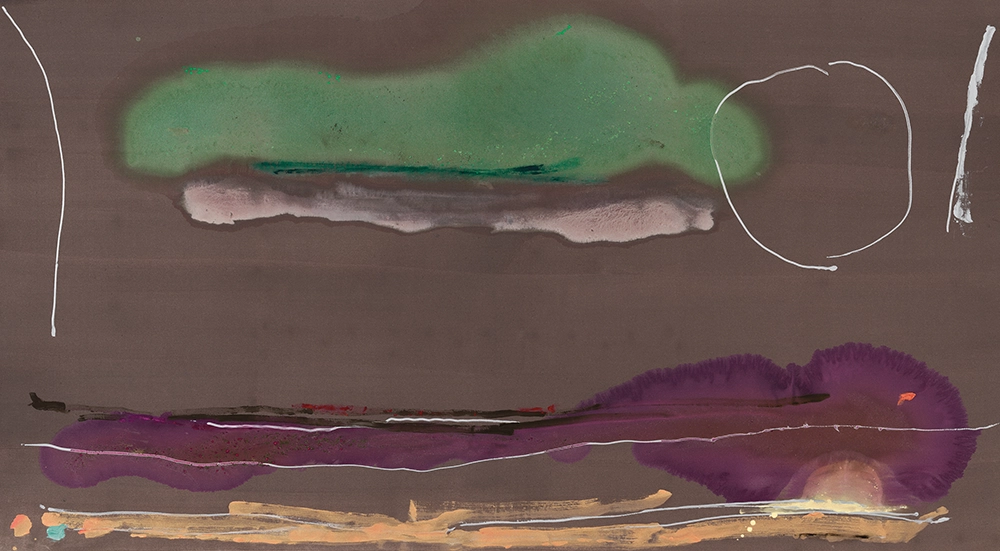

Helen Frankenthaler, The Human Edge, 1967

Sala 3

«[The Human Edge] è stato dipinto nel momento in cui emergeva la pittura minimalista più rigorosa. Sul bordo inferiore c’è una linea a forma di L molto personale, inquieta, non geometrica, non pulita. Quando è arrivato il momento di dare un titolo [al dipinto]… [sapevo che] l’avrei chiamato The Human Edge, perché nel Minimalismo c’era molto che negava la qualità umana, l’elemento umano».

—Trascrizione della conferenza di Palm Springs, 1996.

“[The Human Edge] was painted around the time of the debut of severe minimalist painting. At the bottom edge, it’s a very personal, worried, non-geometric, non-clean line—L-shaped. When it came time to title [the painting] . . . I [knew that I] would call it The Human Edge because there was a lot about Minimalism that removed the human quality—the human edge.”

—Palm Springs lecture transcript, 1996.

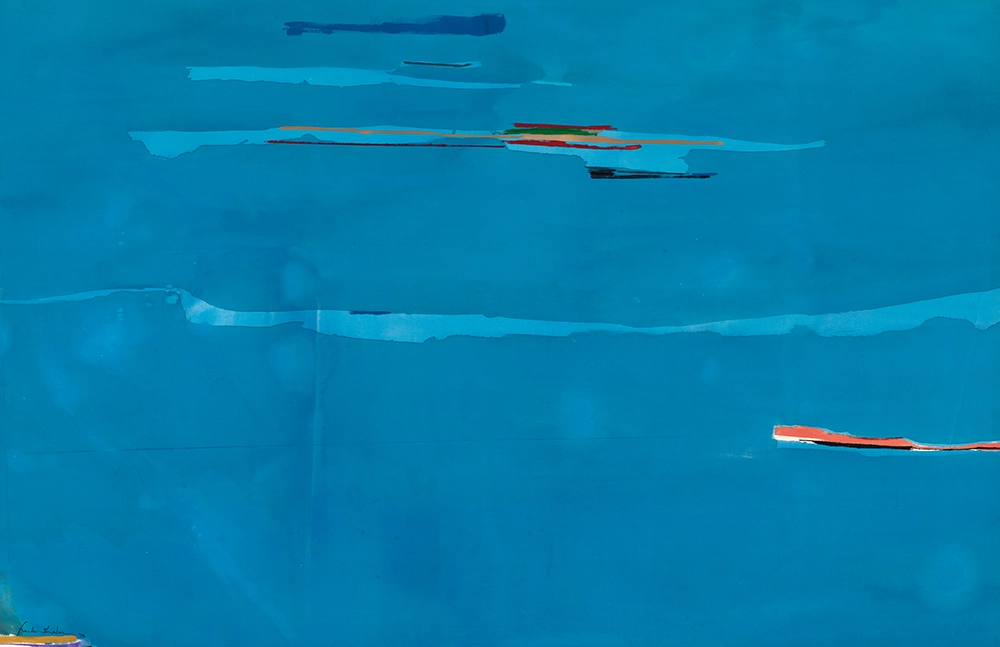

Helen Frankenthaler, Ocean Drive West #1, 1974

Sala 7

«[Il dipinto] è stato realizzato lì [nello studio di Frankenthaler su Ocean Drive West, Shippan Point, Stamford, Connecticut]… Su Ocean Drive West ti ritrovi sempre a fissare la linea dell’orizzonte… Ci sono zone sfocate di Long Island oltre il Sound, alcune sono visibili, [altre] no. Non stavo guardando la natura o un paesaggio marino, ma il disegno presente nella natura, proprio come il sole o la luna possono essere visti come cerchi o alla luce e al buio. Non stavo guardando la natura o un paesaggio marino, ma il disegno presente nella natura, proprio come il sole o la luna possono essere visti come cerchi o come luce e ombra».

—HF in Frankenthaler: A Paintings Retrospective, 1989.

“[The painting] was done there [at Frankenthaler’s studio on Ocean Drive West, Shippan Point, Stamford, Connecticut] . . .On Ocean Drive West you are always staring at horizon lines… There are hazed-out parts of Long Island across the Sound, parts of it can be visible, [other] parts not. I wasn’t looking at nature or seascape but at the drawing within nature—just as the sun or moon might be about circles or light and dark.”

—HF in Frankenthaler: A Paintings Retrospective, 1989.

Helen Frankenthaler, Eastern Light, 1981

Sala 8

«Quando sono in Connecticut [Shippan Point, Stamford], spesso esco sulla terrazza e osservo i continui cambiamenti del cielo e delle maree e ciò che accade ai colori, alle forme e agli spazi. E in qualche modo [trapela] nella mia estetica».

—Joanna Shaw-Eagle, Architectural Digest Visits: Helen Frankenthaler, 1985.

“When I’m in Connecticut [Shippan Point, Stamford], I often go out on the deck and watch the constantly changing skies and tides, and what happens to colors and shapes and spaces. And somehow this [seeps] into my aesthetic.”

—Joanna Shaw-Eagle, Architectural Digest Visits: Helen Frankenthaler, 1985.

Helen Frankenthaler, Cathedral, 1982

Sala 8

«Ho iniziato a usare la pittura [densa] in quelli che chiamo “grumi” … come se si disegnasse in alcune zone di una tela colorata, trattando il resto come se fosse acquerello su carta, cosa che ho fatto per tutta la vita. Penso che concentrarsi troppo su qualcosa solo perché è tela, grande e impegnativa, spesso sia di ostacolo. [È meglio] trattare le cose come se fossero rilevanti, ma non indispensabili».

—Trascrizione della conferenza su Pollock-Krasner, 1994.

“I started using [thick] paint in what I call “clumps” . . .as drawing itself in certain portions of a tinted canvas, treating the rest of it as if it were watercolor on paper, which is something I’ve done all my life. I think [that] bearing down on something because it is canvas and big and serious often gets in your way. [Better] to treat things as if they were important but dispensable.”

—Pollock-Krasner lecture transcript, 1994.

Helen Frankenthaler, Madrid, 1984

Sala 8

«Sono sempre stata sensibile alle meraviglie dell’ambiente naturale. Quando ero bambina portavo mia madre alla finestra della mia stanza nel nostro appartamento al tredicesimo piano di Manhattan e le chiedevo di guardare le nuvole, perché ero incantata da ciò che potevo vedere fuori dalle finestre, dagli spazi e dai mutamenti della natura».

—Intervista di Tim Marlow, maggio 2000, Connecticut.

“I have always responded to the wonders of the natural environment. When I was a child, I used to take my mother to the window of my room in our apartment on the thirteenth floor in Manhattan, and have her look at clouds, because I was so mesmerized by what I could see out the windows, all the spaces and changes of nature.”

—HF interview with Tim Marlow, May 2000, Connecticut.

Helen Frankenthaler, Star Gazing, 1989

Sala 8

«Sento sempre … di avere le mie origini [nel] Cubismo. E ogni volta che sono bloccata… sento che è meglio tornare al familiare… a una strada già percorsa, e che da lì nascerà qualcosa di nuovo. Di solito è la mia via d’uscita. Ne vedo i segni qui, in qualcosa come [quei] rettangoli».

—Intervista di Andrew Forge, trascrizione Yale Art Gallery, 1993.

“I always feel. . . I retain my origins [in] Cubism. And whenever I’m stuck. . . I feel, well, go back to the familiar . . . to a road you’ve traveled and something new will happen from there. That’s usually my way out. I see signs of it here in something like [those] rectangles.”

—Q&A with Andrew Forge, Yale Art Gallery transcript, 1993.