by Ludovica Sebregondi

A hypochondriac, a lunatic, “a trifle wild and strange”, “fickle” or capricious, “inspired and a recluse”: that’s basically the description we’re given of Jacopo Carucci, who was born in Pontormo (Puntormo or Puntorme, the village near Empoli after which he was named) on 24 May 1494. According to Vasari he “never went to festivals or to any other places where people gathered together, so as not to be caught in the press; and he was solitary beyond all belief.” He even displayed an introverted demeanour in his own house, a “building erected by an eccentric and solitary creature,” in which the bedroom was reached via a ladder which Jacopo could winch up to prevent anyone else from entering the room without his knowledge. The building was situated in what was then the Via Laura (now Via della Colonna). It didn’t have much in the way of street frontage but it opened out onto an inner courtyard where Pontormo had a vegetable garden (“I bought canes and willow binding for the orchard”) and fruit trees (“I planted the peach trees in the morning”), and where he sought cool shade in the summer heat (“No sooner had I risen and dressed on Sunday morning than I went down to the orchard where it was cool”).

The kitchen in the house where Pontormo was born. Photo: Comune di Empoli

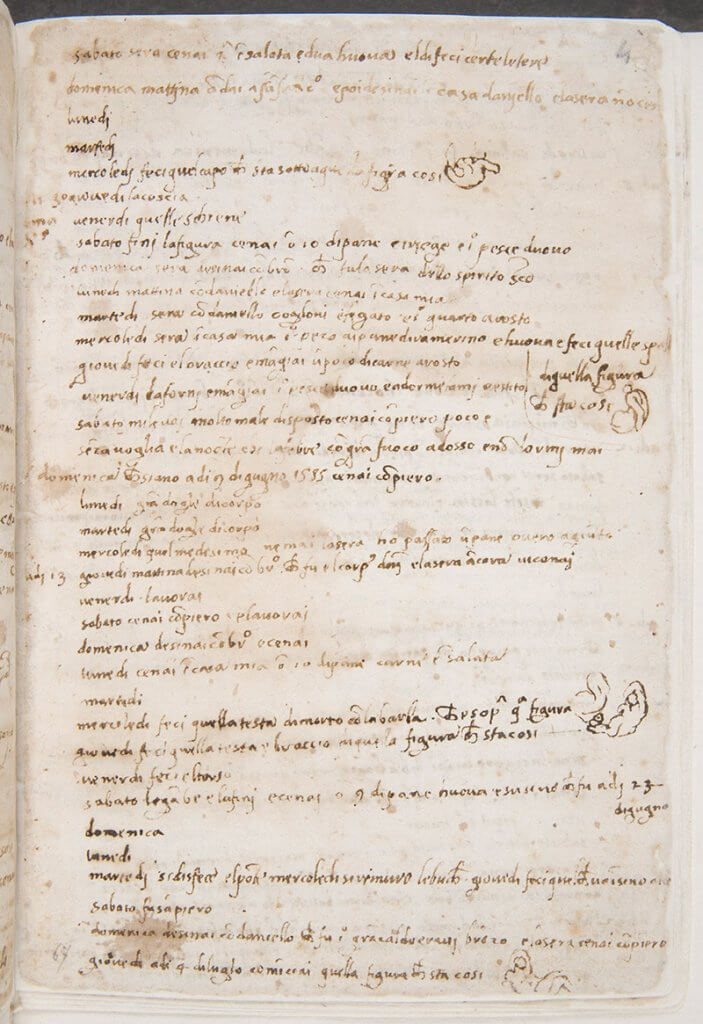

So here we have a man who would have felt very much at home in the “quarantine” situation we’re all experiencing right now. He was a loner, especially during the extremely long stretch that he spent locked away from dawn to dusk behind the planks of a sealed workshop that he set up in the church of San Lorenzo in Florence from 1546 until his death on 1 January 1557. We know quite a bit about the last period in his life – from 11 March 1554 till his death – from a diary in which he jotted down all sort of things about his art, his world and his era. It’s a working notebook, a memoir and a crucial source of information about the eating habits of his day, all rolled into one.

Diary of Jacopo da Pontormo, 1554–6,

Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, ms. Magl. VIII, 1490, c. 67r

Despite his introverted nature, Pontormo had a number of very close friends: thinkers and craftsmen, workers and entrepreneurs, and of course his pupils, including his favourite, Agnolo di Cosimo, known as Bronzino. He ate with them at home and at the tavern, choosing lamb, “black pudding and pig’s liver,” “fried lamb’s liver,” “pork boiled in wine,” “vermicelli,” “boiled pigeons,” “a duck,” an “India hen,” “chicken and veal,” “doves,” “chicken and hare,” “woodcock” and “farciglioni” (waterfowl), a “roll of sausages” and thrushes. He said that “wonderful pancakes” made him a happy man, but he was irritated when bad food made him feel ill: “this evening I ate some poor meat, which didn’t do me much good at all.”

When he was on his own, he’d make mutton broth or (boiled or fried) kid’s head, “offal,” or vegetables such as “good cabbage cooked by my own hand,” but he also ate bread with dried figes and cheese, or peas in the pod with ricotta. He was mad about eggs, “fried,” “in the pan” or “à la egg fish” as omelettes were known in Florence on account of their shape, or eggs with peas, asparagus or artichokes. Greens played a major role in his eating habits – some he grew in his own orchard while others he’d buy at the market – but they were always a “filler”, in other words he’d eat them with bread which was his dietary staple, as indeed it was for most of the population at the time.

Peas in the pod and pecorino. Photo: James O’Mara/O’Mara Mc Bride

To tie in with the exhibition entitled Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, Diverging Paths of Mannerism held in Palazzo Strozzi in 2014, the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi sponsored Maschietto Editore’s publication of Pontormo’s Table. Recipes by great chefs: timeless ingredients and artistic inspiration. Prompted by the consideration that the raw materials of Tuscan cuisine haven’t changed in five centuries, nineteen of the region’s star chefs were asked to come up with a recipe using the same basic ingredients as Pontormo mentions in his Diary. Nineteen star chefs, that is, and one very special figure, Dom Sisto Giacomini, a bibliophile and restorer of books, who offered a recipe in the tradition of the Certosa del Galluzzo monastery just outside Florence, for Trout in Egg White with Marjoram Leaves and Borage Flowers.

Gut a trout, wash it and stuff it with a clove of garlic and a small branch of rosemary; grill it on charcoal and fillet it. Pour a good glug of Tuscan extra-virgin olive oil into a frying pan and add the egg white, a pinch of salt, a few leaves of marjoram and some borage flowers. Place the trout fillets in the pan and place over the heat until the egg white has cooked through.

The recipe is intended to conjure up these words in Pontormo’s Diary: “On Sunday, the 10th of said month, I lunched with Bronzino and in the evening at 11 of the clock I dined on that fat fish and several small fry and I spent 12 soldi, for Attaviano was there; and in the evening the weather began to turn after several days of fine weather without rain.”

Dom Sisto Giacomini at the Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino exhibition, standing in front of Pontormo’s Visitation (1514–16), Photo: James O’Mara/O’Mara Mc Bride

Top: Pontormo, Self-portrait, detail from the Deposition from the Cross, 1526–8, Florence, church of Santa Felicita, Capponi Chapel