by Ludovica Sebregondi

The “great flu” after World War I that cost millions of people their lives throughout the world in several waves between 1918 and 1920 (the actual number of dead is still a matter for debate, much like the figures for the current pandemic) was known as the “Spanish Flu” because it was first reported in the Spanish press. Spain had been neutral during the war and so its media were subject to less stringent censorship.

Luckily, however, the mutual influence traded between the Iberian peninsula and the rest of the world was not restricted to the flu. In fact, in the art world it played an absolutely crucial role in the birth of modern art. American writer Gertrude Stein, a close friend of Picasso, argued that 20th century art was devised in France… but by Spaniards. The Palazzo Strozzi exhibition entitled Picasso and Spanish Modernity (2014–15), curated by Eugenio Carmona, set out to illustrate this astonishing interweave of mutual influence with eighty-eight works (forty-five of which were original Picassos) by thirty-seven different artists, not only exploring Picasso’s impact on modern art in Spain but also, indeed above all, showcasing the most original and significant innovations that Picasso and his fellow Spaniards brought to the international art scene as a whole.

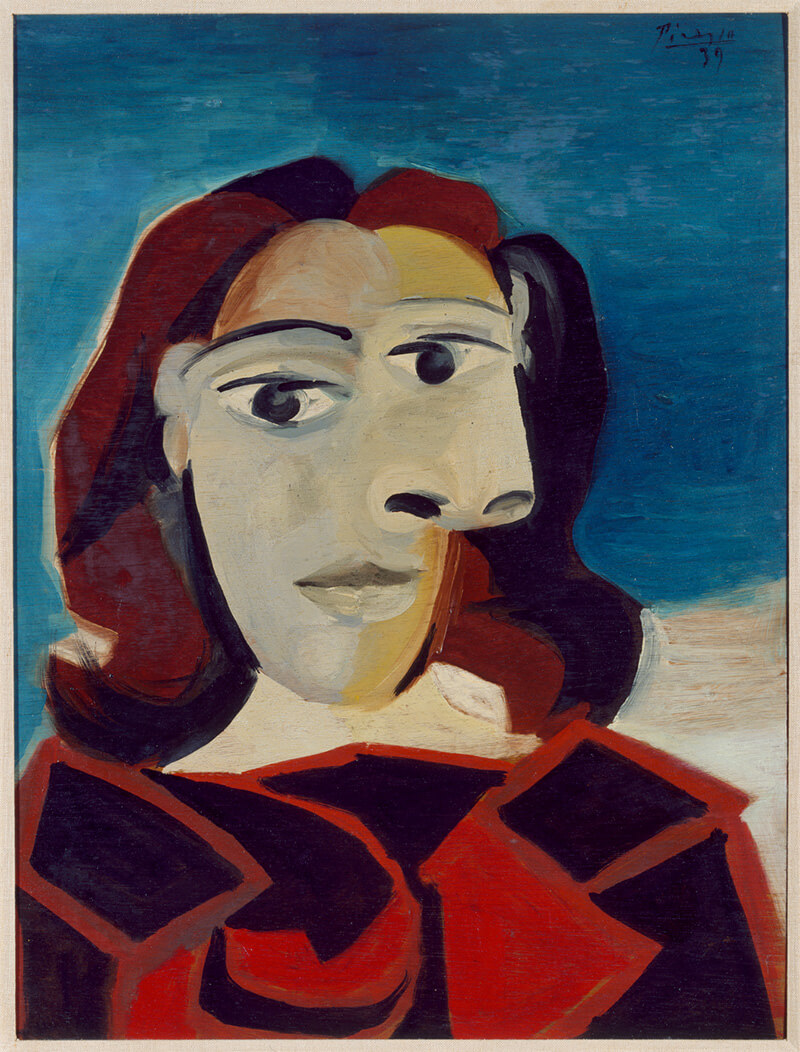

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Dora Maar, 1939, Madrid, Museo Reina Sofía Collection

Working in France in the course of the 20th century, Picasso can be said to have defined the styles through which modern art was to develop. He invented Cubism, he impressed a new meaning on collage and, at the end of World War I, he overturned everything he had done to date by reconciling with classicism, subscribing in many ways to the so-called “return to order.” Yet he was soon to abandon the dialectic between Cubism and classicism, setting off down a new path in the mid-1920s and, like Miró, embracing Surrealism. By the 1930s he was being hailed as a legend of modernity, but with the centre of modern art shifting to New York and the rise of Abstract Art, Picasso ceased to embody “the paradigm,” despite Guernica and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which were on display in New York at the time, having a considerable influence on the Abstract Expressionists.

From the 1950s Picasso became a living legend in his own right, absolute and unquestioned. His work ceased to attract the attention of the new generation of artists and began to be seen as a reflection of the whole of his epic career to date.

The room of the exhibition Picasso and Spanish Modernity dedicated to Guernica. Works from the Museo Reina Sofía Collection in Madrid

Miró was born in Barcelona in 1893 and, like Picasso, he was soon drawn to the artistic ferment and avant-garde work being done in Paris where he moved in 1920, although he remained profoundly Spanish at heart. Despite his encounter with Picasso, with the Dadaists in 1920 and with the exponents of Surrealism three years later, he never strayed from his own “magical and dynamic” world, becoming over time the most influential of the innovating Spanish artists and a beacon, a creator of focal points, for the younger generation. Dalí, for his part, picked up Picasso’s legacy, yet he developed it in a different vein, with a psychological slant that was soon to draw him into Surrealism.

Room housing, on the right-hand wall, from the back, Siurana, the Path by Joan Miró (1917), Peasant Woman Mask by Julio González (c. 1927–9), Harlequin by Salvador Dalí (1927) and Still-life (1926) by Manuel Ángeles Ortiz, another Spaniard who moved to Paris. Works from thel Museo Reina Sofía Collection in Madrid. Photo Filippo Montaina

While Picasso, Miró and Dalí are the Iberian trio virtually par excellence, we certainly should not overlook the work of Juan Gris (Madrid, 1887 – Boulogne-Billancourt, 1927) who, together with Picasso, was part of the system created by the so-called historic Avant-gardes but who remained loyal to Cubism after the war, marking his distance from Picasso who had embraced a classicising figurative art. Nor should we neglect the work of Julio González (Barcelona, 1876 – Arcueil, 1942), who was in Paris by 1900 in the company of Picasso, Braque, Torres García, Gargallo, Brancusi and Max Jacob and who is held to be the inventor of the modern sculpture in iron that was to have such an impact on the whole of the 20th century.

Dalí and Picasso in two still from Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris di Woody Allen (2011)

Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris (2011), with its dreamlike settings and with the ghosts of a glorious past who come back to life at midnight, takes us back to the Roaring Twenties when Paris still lay at the heart of modernity and innovators flocked to it from all over the world. Literature (Hemingway and the two Fitzgeralds) and music (Cole Porter) in the film come from the United States, but the only two figurative artists conjured up in it in the flesh are both Spanish, Dalí and Picasso, while Matisse puts in only a fleeting appearance. And as for the cinema itself, we are given Luis Buñuel! Woody Allen stages a magical era, a “glorious past, now lost” – a recurrent and age-old theme in the human experience if we think of Horace’s “laudator temporis acti” – pointing to the ever fashionable tendency to praise the past by comparing it with a tawdry present. In this case, however, the adjective “fabulous” that is so often attached to the 1920s is justified by the outstanding creativity of a period that owed its renown to the crucial influence of Spain rather than to the lethal pandemic that took its name from that country.