by Ludovica Sebregondi

One of the things we hear most often in these days of isolation is the hope, reflecting a basic human need, that we can soon embrace our loved ones and friends again physically rather than just virtually. Until only a few months ago we barely gave it a second thought when we shook hands or embraced whenever we met someone, then embracing gradually became rarer and so did shaking hands, even though the gesture was instinctive while holding back demanded rational thought.

Being physically “in touch” was normal, but now we sorely miss those displays of closeness. Our present situation can also prompt us to take a fresh look at those works of art that have sought to convey this physical contact, each one in its own way and each imbued with a different emotional condition, be it sacred, dramatic or sensual.

Bill Viola, The Greeting, 1995, Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Pontormo, Visitation, c. 1528-1529, Carmignano, Pieve di San Michele Arcangelo, Photo Antonio Quattrone

The Bill Viola. Electronic Renaissance exhibition held in 2017 conjured up an astonishing dialogue between the historical and the contemporary by juxtaposing some of the artist’s works with masterpieces by those masters of the past to whom he had turned for his inspiration in the course of his artistic career. In exploring spirituality, experience and perception, Viola probes mankind: people, bodies and faces are the leading characters in his poetic and highly symbolic work. He does not simply emulate the old masters, he revisits them. The women in Pontormo’s Visitation, united in a kind of dancing embrace reminiscent of the Three Graces, also number three: Elisabeth on the right and Mary on the left are shown in profile, while Elisabeth’s alter ego is seen full-face in the centre. The fourth figure on the left, in pink, is set slightly apart and does not appear to be fully involved in the meeting. That was certainly one of Bill Viola’s intuitions, at any rate, and so he cut the number of figures down to three, focusing on the relationship between them and on their different emotions, allowing us to perceive each detail in extremely slow motion and turning each still into a painting in its own right in an allusion to the great tradition of Western art. A scene of a few seconds is drawn out thanks to this extremely slow motion: what the artist is attempting to do here is to capture a specific, simple, daily event – women meeting – in order to highlight the complex inner and social dynamics underlying such a run-of-the-mill occurrence.

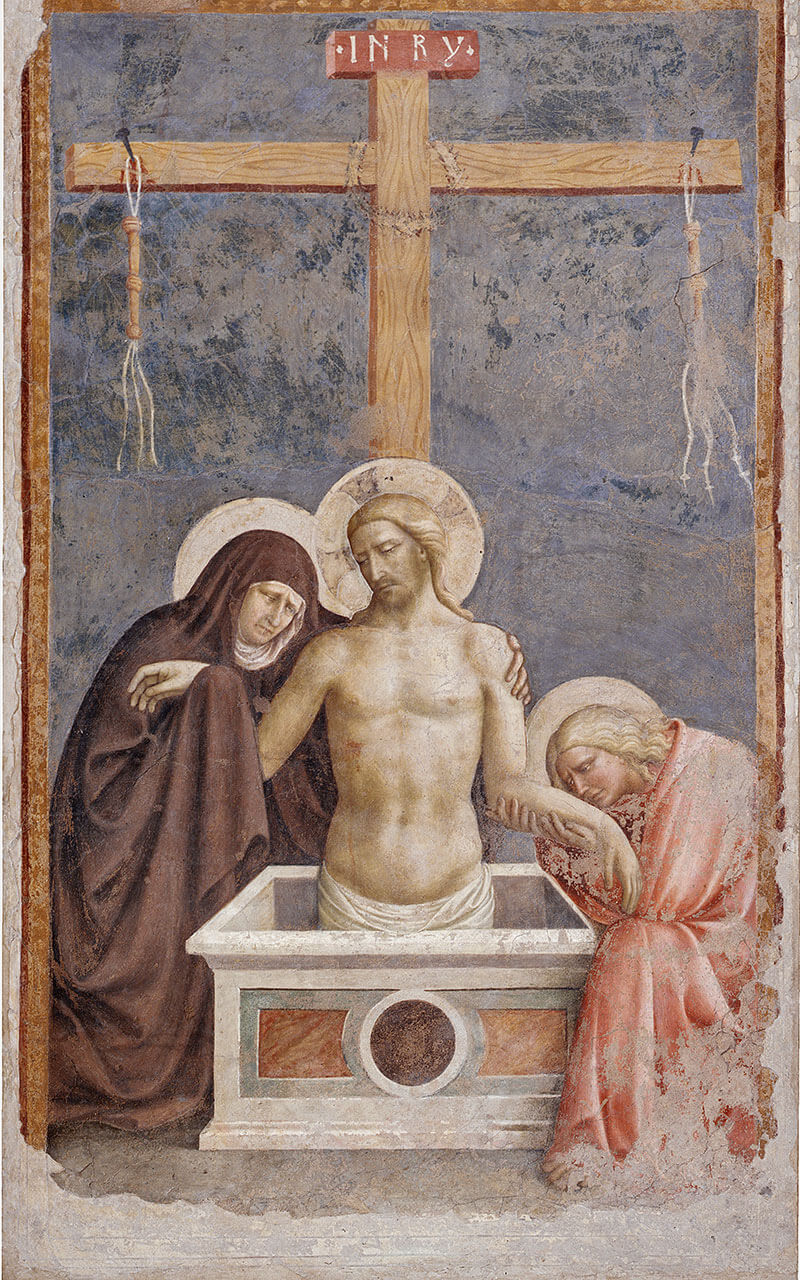

There are countless depictions of the Virgin embracing the Christ Child in the most natural of human gestures, a mother holding her small child close, yet they are veined with the melancholy that comes with foreknowledge of the future, and there are an equally large number of images of the Passion, with Mary grieving as she holds the body of the dead Christ.

Bill Viola, Emergence, 2002, Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Masolino da Panicale, Christ the Man of Sorrows, 1424, Empoli, Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea, Photo Antonio Quattrone

In his video entitled Emergence, Bill Viola cites Masolino da Panicale, despite other illustrious sources of inspiration stretching from Roman sarcophagi, via Raphael’s Deposition, to Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat, but the artist’s initial inspiration came from a photograph in the papers in which two women were lifting up a dead man’s body. Viola was reminded of Masolino’s work and this spawned a production with actors and stage props, where the shape of a Renaissance tomb merges with that of well and the presence of water brings a symbol of life to the image of death alluding, in a Christian vein, to the Resurrection.

These images, however, are at variance with others of an erotic nature that borders at times on the incestuous. The Cinquecento in Florence. From Michelangelo and Pontormo to Giambologna (2017–18) exhibition highlighted the immense freedom of expression displayed by the same artists in addressing both sacred themes and secular subjects of a sensual nature, casually switching from the devout to the lusty and back again. Thus Alessandro Allori (Florence, 1535–1607), an artist capable of exploring religious themes in intimate depth, shows us, in his Venus and Cupid, a mother and child involved in a tussle for possession of a bow, interpreting the subject in an erotic and sensual vein to convey a moment of intimacy and physical contact between the two figures.

Alessandro Allori, Venus and Cupid, c. 1575-1580 circa, Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole, Musée Fabre, inv. 887.3.1

Vincenzo Danti (Perugia 1530-1576), Leda and the Swan, 1570, marble, London, Victoria and Albert Museum. Purchased by the John Webb Trust, A.100-1937

Vincenzo Danti (Perugia 1530–76) goes even further in his rendition of the subject of Leda embracing Zeus in the shape of a swan, an embrace heralding their lovemaking. Florentine art in the latter half of the 16th century explored the mythological and allegorical repertoire in conflicting ways, presenting figures – arranged in elegant and complex compositions with their often contrasting poses – in which erudite reference sits cheek by jowl with unashamed sensuality.