by Arturo Galansino, Ludovica Sebregondi, Riccardo Lami and Matthias Favarato

Eighty-four days separate Sunday 8 March, Palazzo Strozzi’s first lockdown day, from Monday 1 June, the day the Tomás Saraceno. Aria exhibition reopens. “Phase Two” in the era of COVID-19 is beginning for Palazzo Strozzi too, as we reassess and rethink our IN TOUCH online project to bring it into line with this new development.

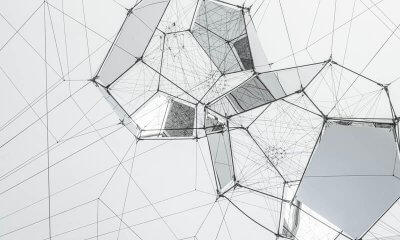

IN TOUCH was an immediate, spontaneous response with a strong sense of urgency at a time of total uncertainty as to what was going to happen in ensuing weeks. We were determined from the outset to react to this crisis with a clear goal, which was to stay in touch with our visitors – to protect our bond of proximity at a time of deep insecurity for all of us, as our normal bearings came under severe strain in this new and utterly unprecedented situation. The Tomás Saraceno’s exhibition offered us the perfect starting point; in fact it was almost prophetic in its reflection on the fragility of our world. Comparison with a spider’s web to illustrate the environment we live in, a concept that plays a major role in Saraceno’s art, is well suited to define the network of relations that have kept us united at this time – a network linked to the online world on which all our daily activities, including our thirst for culture and beauty, have had of necessity to pivot during lockdown.

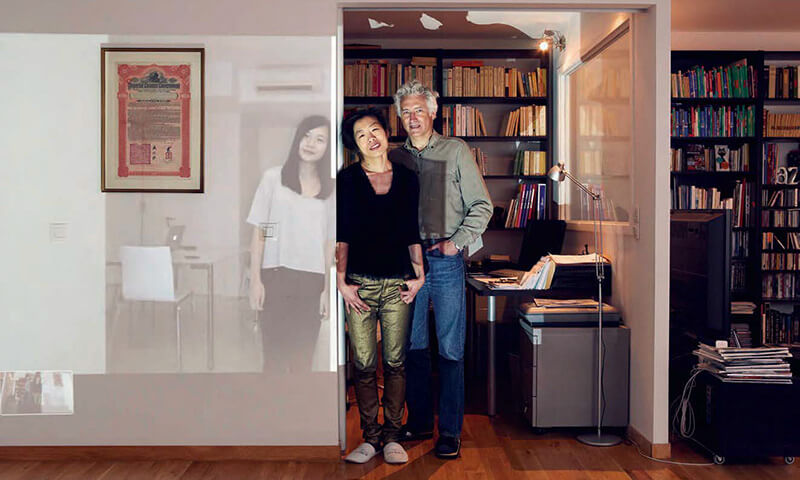

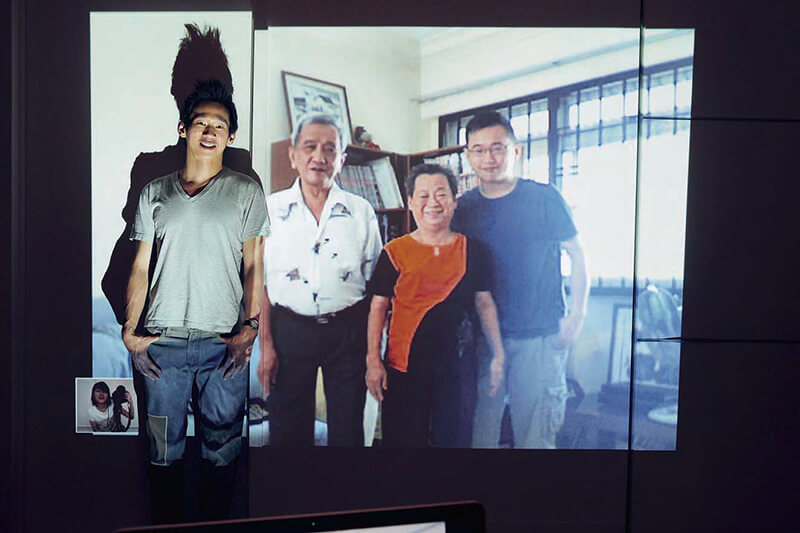

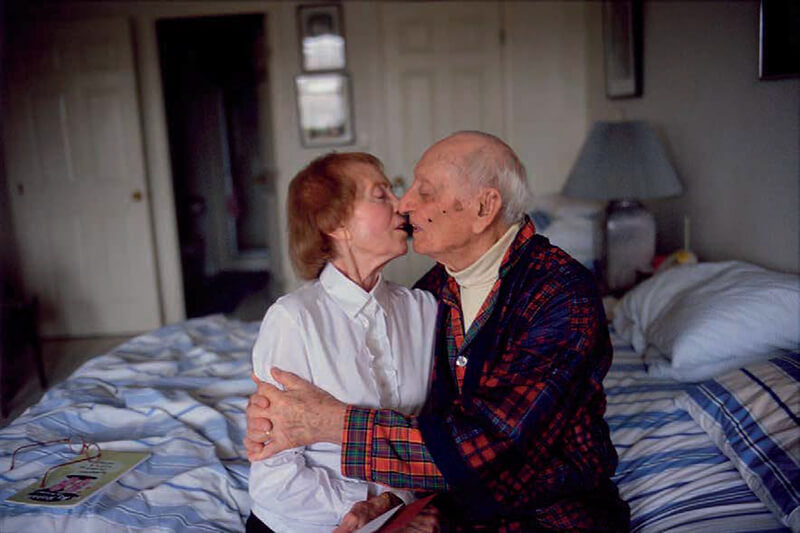

Our choice for the IN TOUCH project was to merge our website and social channels by creating new and original content taking a fresh look at certain moments in Palazzo Strozzi’s history, rather than simply taking a stroll down memory lane, in an effort to discover new values in them in the light of our present circumstances. This led us to address such eminently topical issues as interconnection, isolation, the sense of nationhood and community, the family and inclusiveness. To address as broad an audience as possible we hosted different viewpoints, as you can see from the authors of the essays (from both within and outside the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi), with whom we were eager not to look backwards into the past but always forwards at the present and into the future. A crucial role was played by the video messages sent in by artists wishing to testify their closeness with Palazzo Strozzi in consideration of their strong bond with us and with Italy as a whole. Marina Abramović, Ai Weiwei, Jeff Koons and Tomás Saraceno all aired their support for us and their contributions proved hugely popular, with Marina’s message in particular attracting almost 1 million hits.

But there are other figures that can help us tell the story of this project too. On our IN TOUCH platform we published 24 essays read by almost 60,000 single users. On Facebook and Instagram we published over 100 posts, reaching over 1.5 million people and causing our online community to grow by 10% in a mere two months. In addition to which, the fact that our visitors spent longer than average on the pages of IN TOUCH is another extremely interesting development because it shows that people preferred to focus on exploring the content in depth rather than simply skimming over it; and this, despite the moment of frenzy everyone was experiencing in the consumption of online content. The top five most avidly read articles were We’re All in the Same Boat; The Shattered Embrace; Dining with Pontormo; Men, Apricots and Cows; and Heaven in a Room. Far from being a mere hit parade, however, this list perfectly mirrors the multi-faceted nature of our approach and the variety of our readers’ interests. A project that deserves a special mention here is the remote-educational project that we christened ART AT HOME for families with children and teens on their hands. The project was visited by almost 6,000 users, many of whom then sent us in the results of their various activities. And we also very much appreciated the affection and esteem displayed by those who have been following our initiatives for a long time, given that the newsletter was the tool most widely used for accessing IN TOUCH, thus highlighting our audience’s closeness even at a time of physical distancing.

And now, as the exhibition gets set to reopen on 1 June, we are about to launch a new phase for IN TOUCH too, turning it into a fortnightly column. Like every cultural institution eager to talk about its own era, Palazzo Strozzi is committed to addressing the most relevant and topical issues of our time, so that every exhibition and activity we produce provides us with an opportunity to explore the world we live in an increasingly contemporary vein. Over the next few weeks we will be pursuing our IN TOUCH project by seeking inspiration in what Tomás Saraceno has called “visions of the future and of reality.” We will be discussing the exhibitions, activities and daily life of Palazzo Strozzi in an effort to keep open a space for parallel debate, a place for cross-contaminating and sharing different points of view.