by Martino Margheri and Caterina Taurelli Salimbeni

Anthropocene is a word that has been abundantly used in recent years as a title for exhibitions, films and publications, yet when it first appeared in a scientific capacity in the 1980s it failed to arouse a great deal of interest. Paul Crutzen, a Nobel prizewinner for chemistry and a leading student of the earth’s atmosphere, began to use it in his academic work, thus spawning its gradual adoption and dissemination.

Crutzen argued that human behaviour was altering the atmosphere and the earth’s crust to such an extent that man could be considered a geological agent in his own right. An analysis of the phenomenon required a definition capable of identifying this new geological era and so the term Anthropocene was born.

Now an accepted term that figures in the dictionary, Anthropocene means a recent era with a human footprint or, more extensively, it indicates the era characterised by the human species’ devastating impact on the planet. The causes can be traced back to our constant increase in hydrocarbon and carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere and to our unbridled exploitation of the world’s natural resources.

There are various theories regarding the start of the Anthropocene but a majority within the scientific community agrees on the symbolic date of 16 July 1945, the day that saw the first ever atomic test at Alamogordo in New Mexico. From that moment on the air has undergone a growing contamination process whose impact we can see on the life of living beings today.

“We need to change our behaviour and to stop using the planet’s water and atmosphere as though they were a rubbish bin”.

interview with Paul Crutzen (TG2, 12/10/2006)

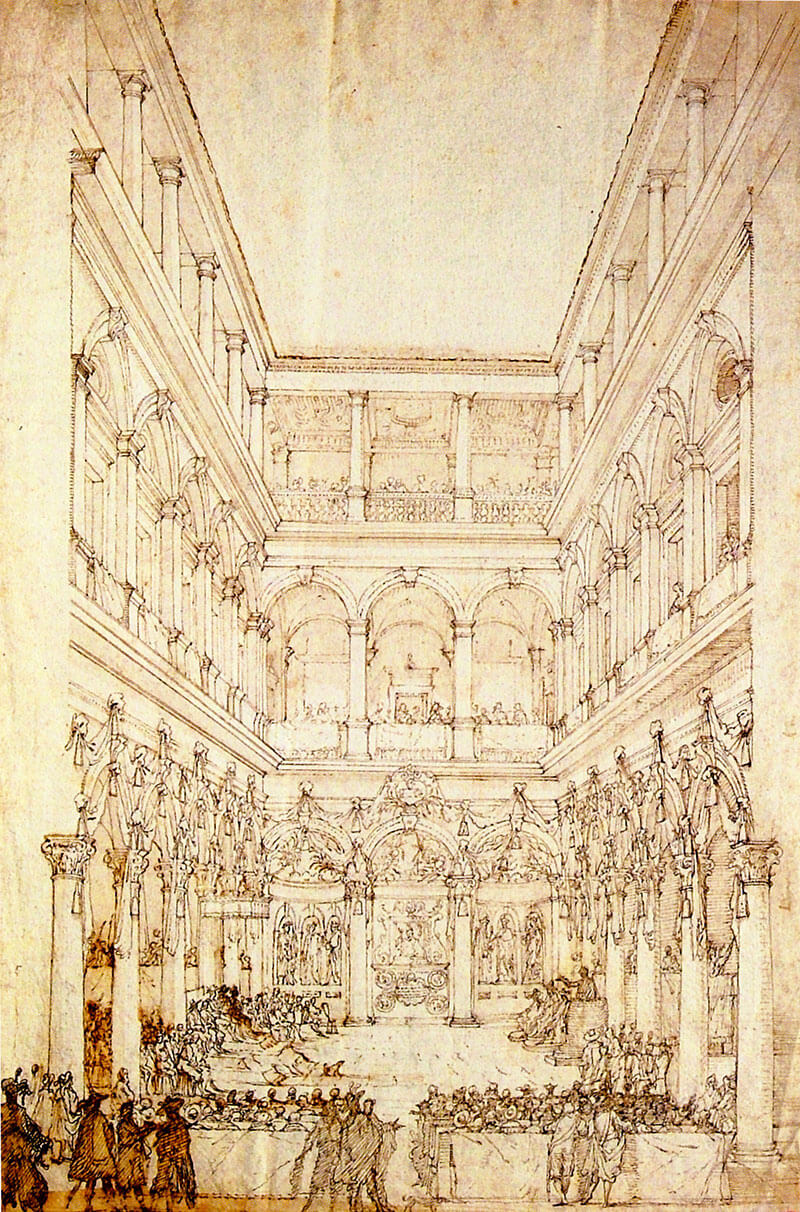

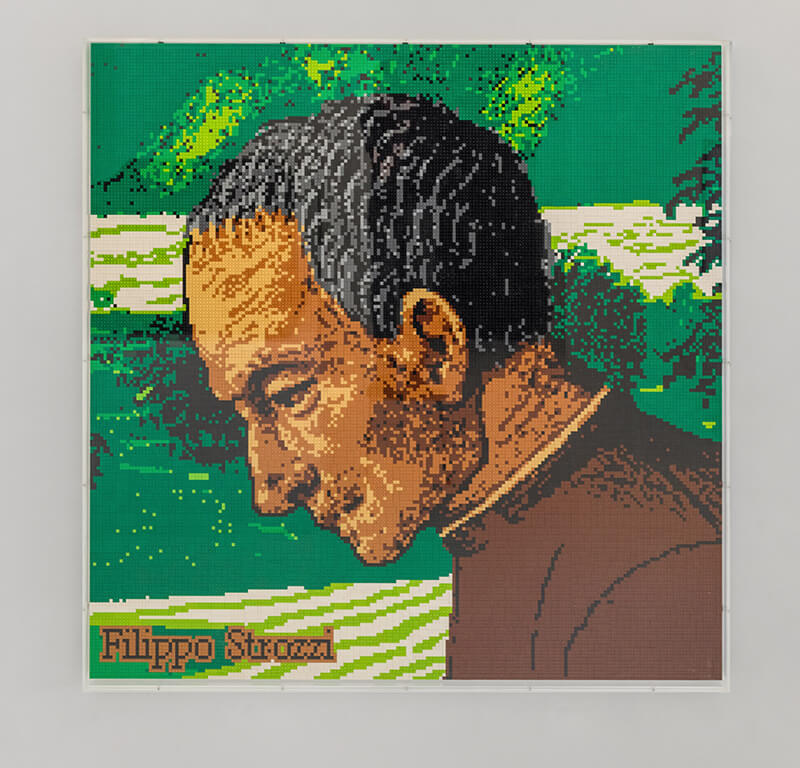

The Anthropocene is not an inevitability. We have shaped it with our own choices and our own actions. Palazzo Strozzi’s exhibition Tomás Saraceno. Aria takes its cue from an awareness of that fact, from a rethink of our way of acting, from the ability to observe phenomena from a different viewpoint and from the possibility of emerging from the Anthropocene by developing new ways of thinking.

Buckminster Fuller, an American architect and philosopher renowned for his experiments with geodesic structures who influenced Saraceno’s thought and work, argued that it is not possible to change things by fighting against existing reality. To change them, you have to build a new model that consigns that reality to obsolescence.

Tomás Saraceno’s art may be visionary and utopian in nature, but at the same time it is as pragmatic and as practical as Buckminster Fuller’s thought. Emerging from the Anthropocene and rediscovering a sense of harmony with planet Earth is more than just a philosophical aspiration, it is a fully-fledged project that is explicited in numerous ways. One of its most complex developments is the Aerocene: an interdisciplinary artistic community working on new expressions of ecological sensitivity with the aim of triggering ethical collaboration with the atmosphere and the environment for a new age free of fossil fuels.

As Saraceno says (in the interview you can find below):

“no one seems to be able to imagine that the heat provided by the sun could allow us to rise up from the earth and allow us to fly in the air. What could we become with a direct relationship with the Sun and the wind, and what society could we prove capable of developing if we envisage different models of mobility?”

Tomás Saraceno x Aerocene, Aerocene Archive(s), 2020. Video, 1’48” (colour, stereo, HD 1080p, 16:9)

Film by Aerocene Community, produced by Studio Tomás Saraceno in collaboration with Art/Beats, Courtesy the artist and Aerocene Foundation

These questions have found a practical answer in the activities of Aerocene which organises the launch of aerosolar sculptures capable of flying thanks to the heat of the Sun and to the infrared radiations emitted by the Earth’s surface: no engines, no batteries, no fuel, no exploitation of resources, only the planet’s own energy. The community’s commitment has consolidated over the past five years and launches have taken place all over the world, while aerosolar sculptures have been designed with a variety of different features: some can be flown like kites, some can travel freely from one city to another by following the course of the winds, and there is even a version capable of lifting a person to a height of over 200 metres and moving him or her over a distance of almost two kilometres.

Men and women have always dreamed of flying and the Aerocene community is succeeding in that undertaking by resorting to forms of energy that promote environmental awareness and preserve the air that we all breathe.

Aerocene Explorer launch. August 7, 2017, Salinas Grandes, Jujuy, Argentina

With the support of CCK Buenos Aires, Courtesy the Aerocene Foundation e CCK Agency, Photography Studio Tomás Saraceno, 2017

To achieve these goals, in 2015 Tomás Saraceno created the Aerocene Foundation which works in close cooperation with an international community of scientists and activists. Prior to that, in 2012, the artist turned to researchers with the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST) in an effort to find an answer to one ot his (seemingly utopian) questions: “Is it possible to fly around the world using the sun as one’s sole source of energy?”

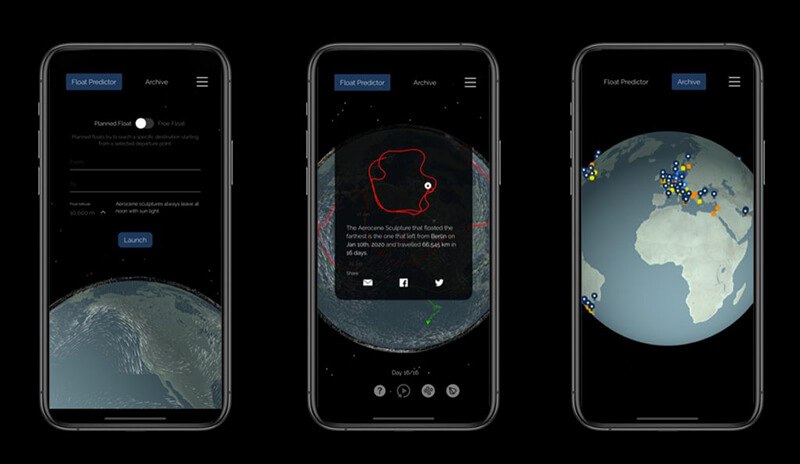

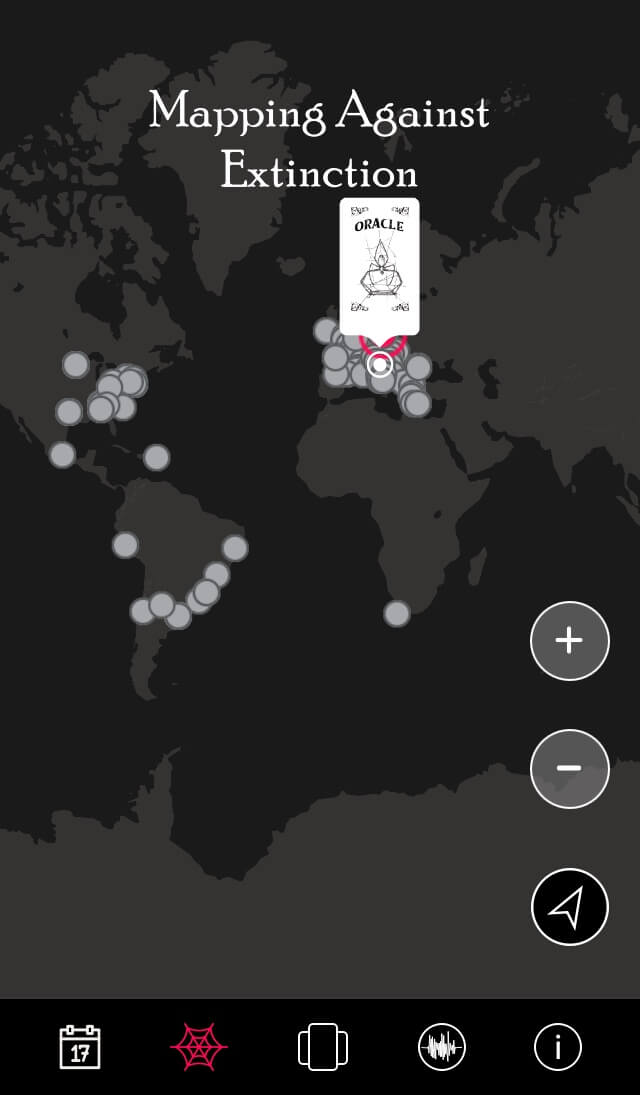

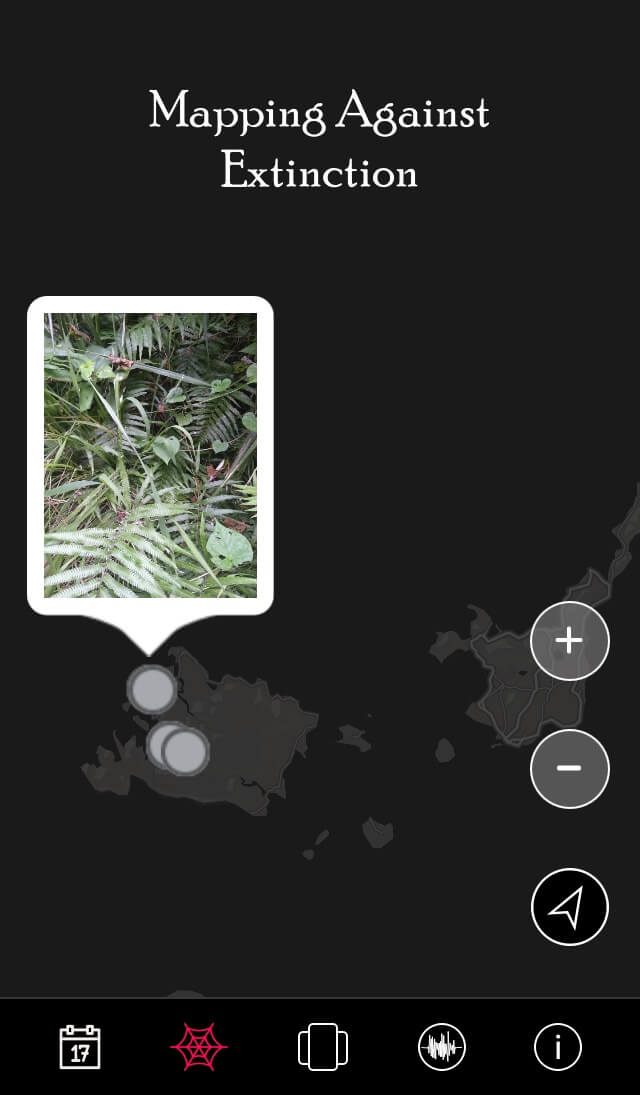

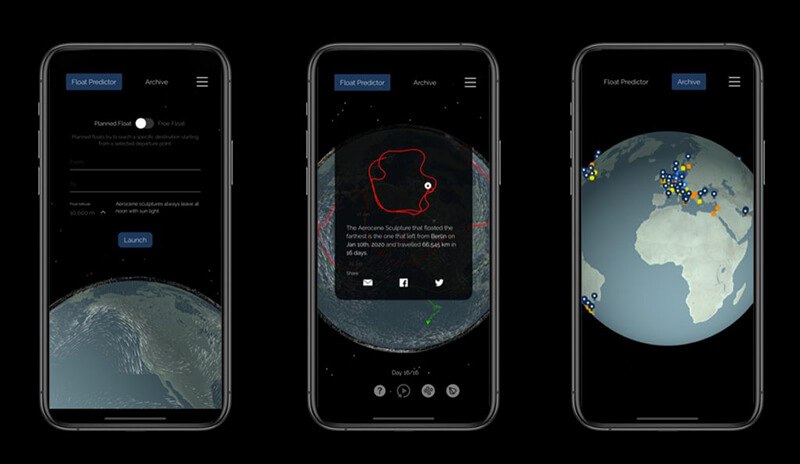

That encounter was to spawn the Aerocene Float, a tool that analyses wind currents and maps out flight paths. A new resource recently perfected by the Aerocene community is the Float Predictor App. This application, available for iOS and Android, performs multiple functions: it allows you to simulate aerosolar sculptures’ virtual flight paths without any CO2 emissions, using freely available meteorological data; it allows you to visualise the Aerocene community’s tentacular presence throughout the world; and it allows you to see the various different kinds of aerosolar sculptures, where they have flown over the years and where the largest numbers of them may be found.

The message is clear: we are a numerous community open to cooperation and bent on changing both the way people move and their relationship with the planet, Technology offers us the opportunity to interact with others and to strengthen our projects in perfect DIT (Do it Togehter) spirit.

Aerocene App (2020) has been developed by Aerocene Foundation in collaboration with Studio Tomás Saraceno.

Courtesy Aerocene Foundation

“Doing it together” was also the driving force behind the cooperation between the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi and the Manifattura Tabacchi. The Manifattura has shown its support for the Tomás Saraceno exhibition by hosting a selection of videos, publications, materials and workshops devoted to exploring the Aerocene philosophy in some depth.

Sustainability, the relationship between man and nature and the construction of the community and of alternative forms of living and of interaction are crucial themes to which the Manifattura Tabacchi is not only sensitive but to which it has entrusted the construction of experimental and innovative forms for the production and enjoyment of art. The link with Tomás Saraceno’s work is confirmed not only in these themes but also in its subscription to the process of overcoming barriers, of audience involvement and of the integration of different disciplines both inside and outside the world of art.

The Manifattura Tabacchi is a large factory built in the western suburbs of Florence in the 1930s and decommissioned in 2001, which now lies at the heart of an ambitious urban regeneration scheme aiming to breathe life into a new city neighbourhood enlivened by a centre for contemporary culture and art complementary to the historical city centre, open to the region and connected to the world. The interdisciplinary art project currently comprising residences for artists, independent spaces, festivals and workshops, is the ideal setting for cooperation between the Manifattura Tabacchi and the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi.

Manifattura Tabacchi aerial view. Photography by Marco Zanta

The chimney courtyard, overlooked by the two buildings converted for temporary use, leads into an area for study, recollection and observation designed and laid out under Tomás Saraceno’s watchful gaze. One’s attention is immediately drawn to the Aerocene Explorer Backpack: a starter kit designed to be worn like a backpack containing everything required for an aerosolar sculpture’s flight experience.

Aerocene Backpack, 2016-on going. Exhibition view, Manifattura Tabacchi. Photography by Alessandro Fibbi

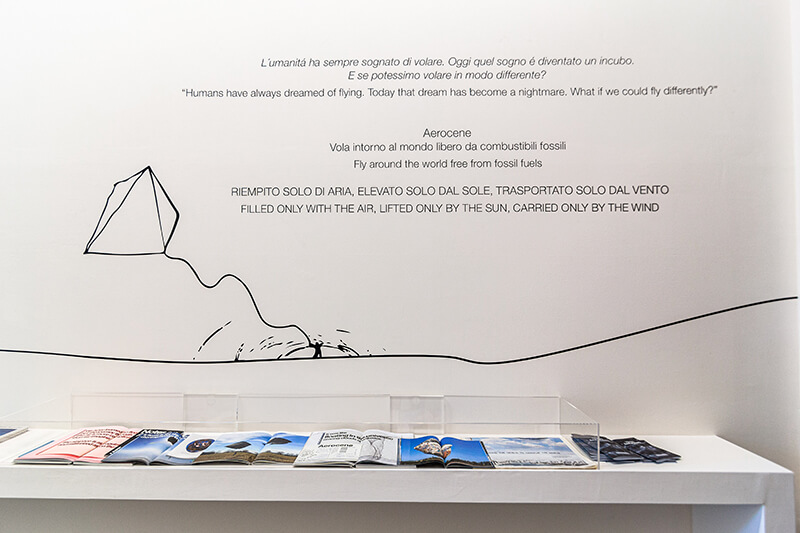

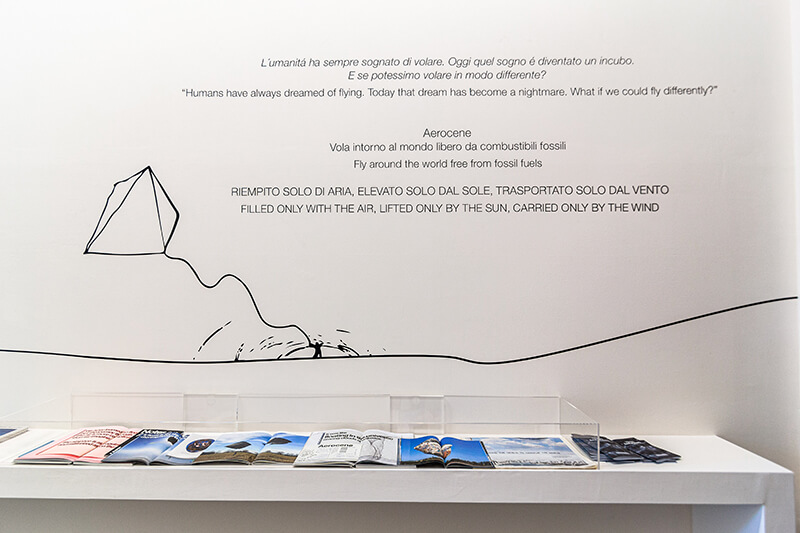

Aerocene publications. Exhibition view, Manifattura Tabacchi. Photography by Alessandro Fibbi

The wall hosts a reproduction of the Aerocene Manifesto that attracts “the attention of all those who hold the atmosphere dear”; the text states that it sees “space as a commonly-owned, physical and imaginary area free from the control of large corporations and from government surveillance. Aerocene promotes free access to the atmosphere, unregulated by tight security measures, It is a proposal, a stage in the air, on the air, for the air and with the air”.

The Manifesto, a political and ethical statement, is the starting point for all the community’s projects. The materials on display at the Manifattura Tabacchi include the possibility of consulting a broad range of publications illustrating the myriad different aspects of Aerocene’s projects.

The discovery tour continues in a screening room where you can immerse yourself in a selection of videos and documentaries on the artist and imagine personally living the flight experiences that you have read about in the publications.

Your gaze tracks children, adults, senior citizens and entire communities as they the aerosolar sculptures together in some of the most fascinating places on Earth. These evocative images cannot help but remind us of the wonders of the world we live in and of the beauty involved in taking care not only of nature but also of people.

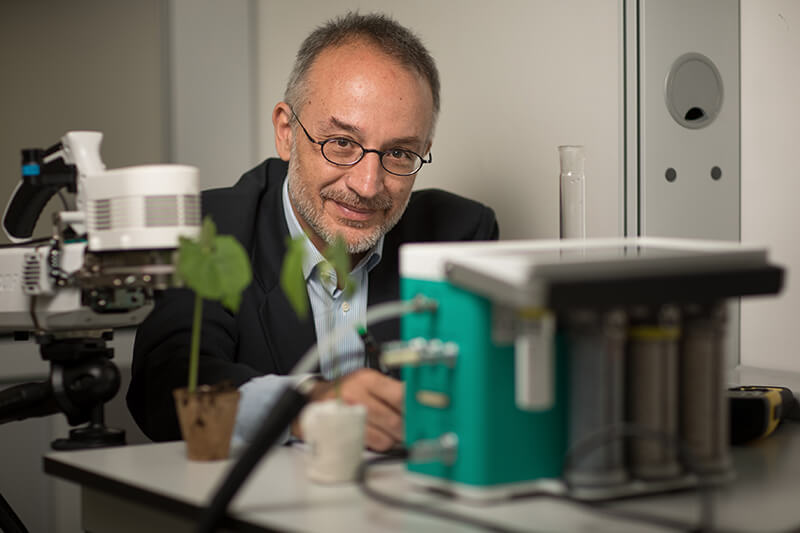

At 18.30 on 13 May Facebook pages of Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi and Manifattura Tabacchi will be hosting a conversation between artist Tomás Saraceno, Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi General Director Arturo Galansino (Direttore Generale, Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi), LINV International Laboratory of Plant Neurobiology Director Stefano Mancuso and Lisa Signorile (biologist and scientific journalist), focusing on art, nature and the collective effort to rethink our way of living and of interacting with the planet.