by Martino Margheri

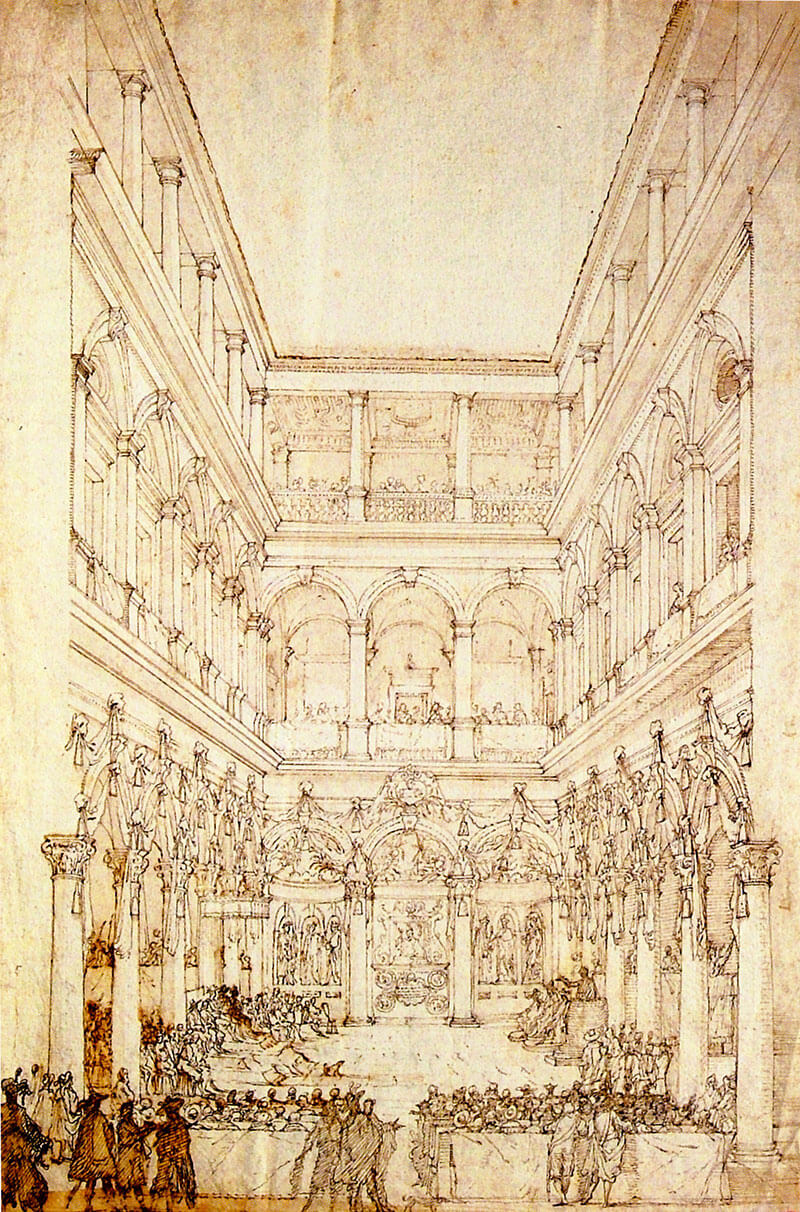

People who work in museums and cultural institutions are more than familiar with the endless timing involved in planning an exhibition. Whether it’s an exhibition of old master works or a monographic exhibition focusing on a leading contemporary artist, preliminary meetings can be held up to four years before it’s due to start. For the Tomás Saraceno. Aria exhibition, initial discussions with the artist and his studio began in 2017 and Saraceno conducted his first exploratory tour of Palazzo Strozzi in the autumn of 2018. Once a project’s broad outline has been defined, discussions get under way with all of the cultural institution’s various departments. The idea is to get the most out of the exhibition, to exploit its full potential by developing activities and strategies concerning every aspect of the work, from communication and promotion to educational projects.

Working with Tomás Saraceno offered us a major opportunity because his studio comprises so many different professional figures: architects, video makers, designers and layout planners who teamwork with the artist and help to breathe life into his vision. Amid the variety of the projects produced by Saraceno and the Aerocene Foundation set up in 2015, we identified experiences that would allow us to experiment with interesting educational formats we could propose to communication and design students to tie in with the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition.

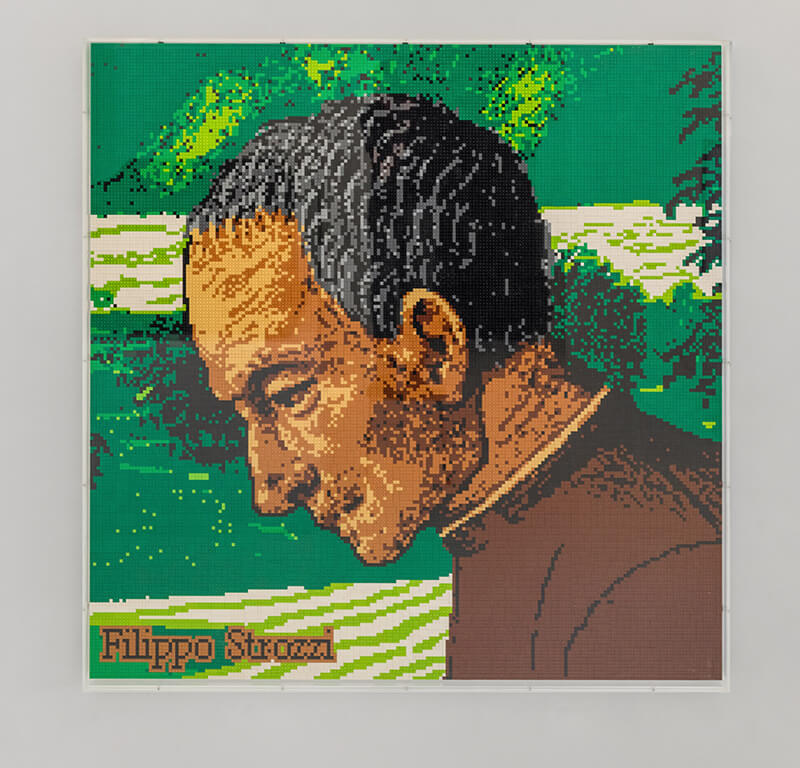

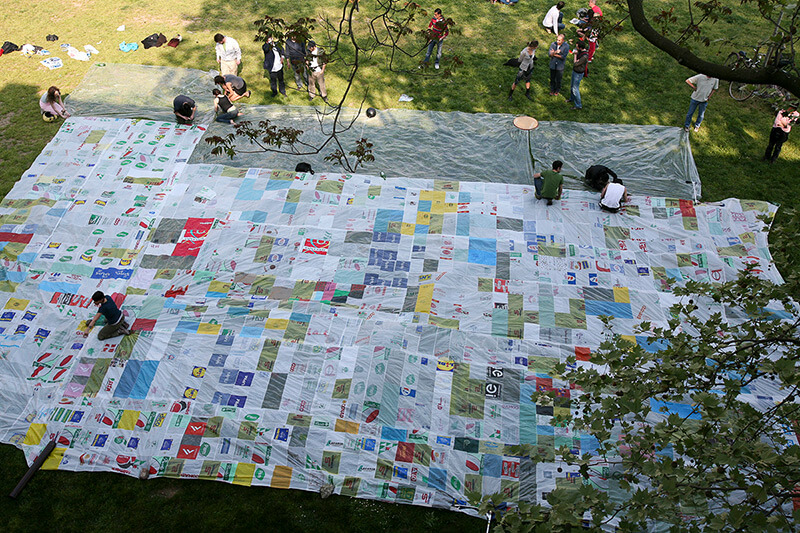

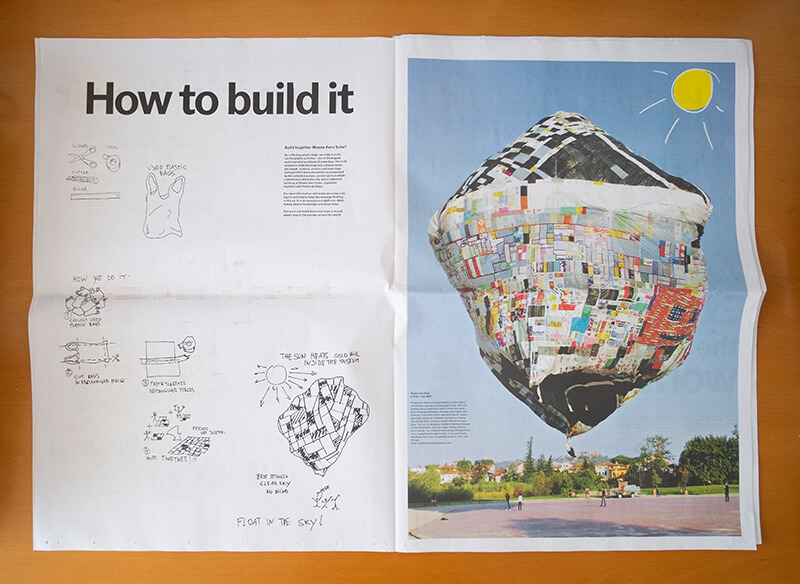

This triggered a dialogue with IED Firenze (Istituto Europeo di Design) which rapidly turned into a substantive institutional partnership and a project entitled Museo Aero Solar with a select group of teachers and students. The Museo Aero Solar is a large flying sculpture made up solely of reused plastic bags. The project first saw the light of day in the course of a conversation between Tomás Saraceno and Alberto Pesavento in 2007, and it has been produced in a variety of formats in over twenty-one countries since then. The Museo Aero Solar embodies the vision of a future without pollution through the growth of the spontaneously created and geographically distant communities that take part in it.

Museo Aero Solar, photographies by Studio Tomás Saraceno, courtesy Aerocene Foundation

On that basis, we set ourselves the goal of involving Palazzo Strozzi’s visitors in the production of a major participatory project for Florence that would start by collecting plastic bags and end with an experimental flight in the Cascine park. But how should we go about doing that? What tools should we use to achieve that goal? What technical skills would we need to build a flying sculpture?

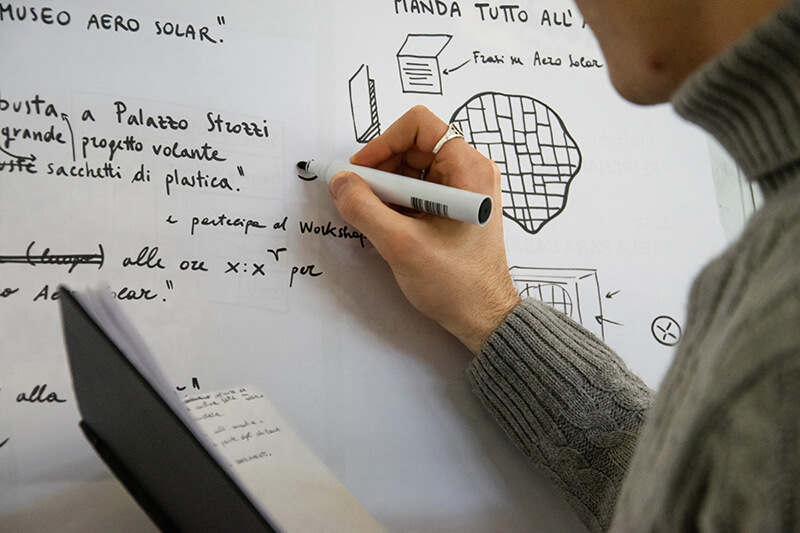

The most important thing to do first and foremost was to analyse the identity and characteristics of the Museo Aero Solar in Tomás Saraceno’s own artistic experience. An introductory lecture with the IED students allowed us to address both the project’s conceptual side and its technical requirements. The debate rapidly led us to the crucial question: how were we going to produce an Museo Aero Solar in a city? How should we communicate it? How could we involve people in the various phases?

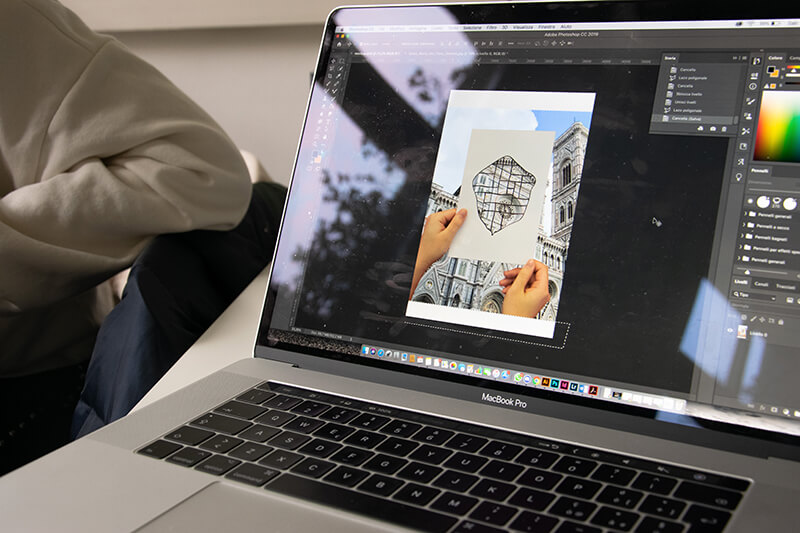

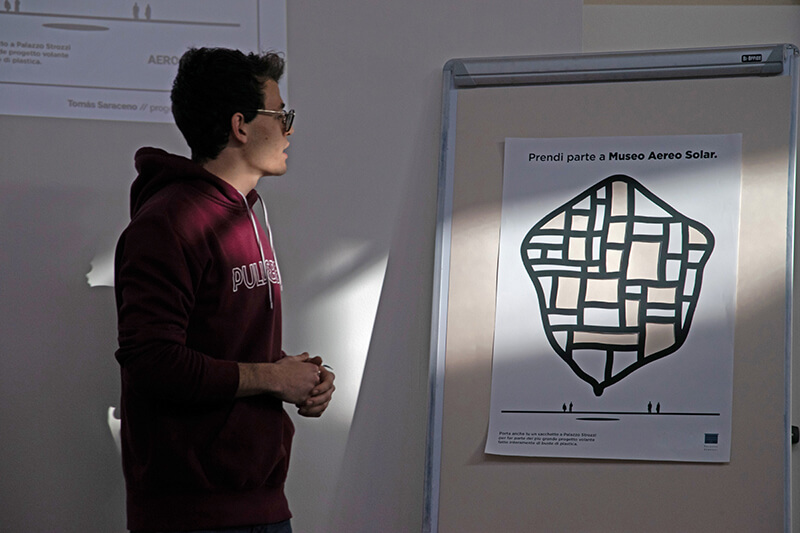

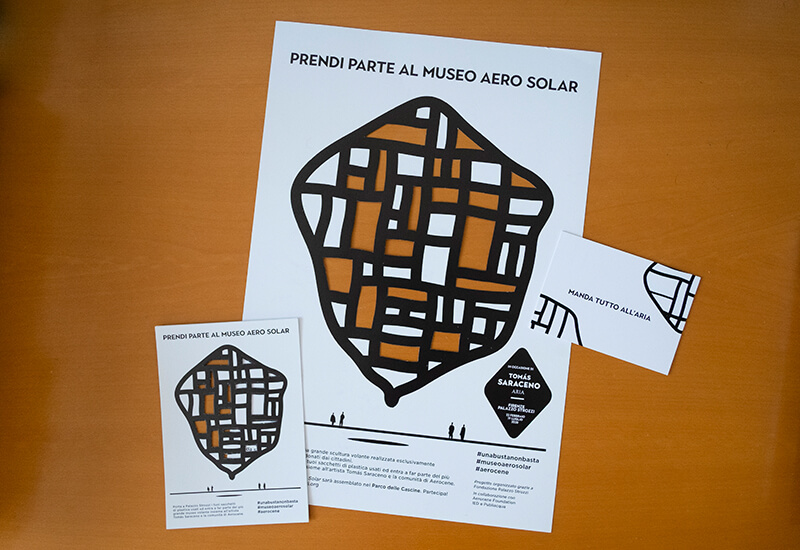

We began to work on developing a single graphic style for postcards, flyers and posters for libraries, schools, universities and academies. The communication would need to convey three crucial aspects: acquainting people with the project, encouraging the collection of plastic bags and inviting people to the grand final assembly and flight workshop.

Communication development and design meeting with the students of IED Firenze

Using the same coordinated image, we worked on the design of a large container in which visitors to the exhibition would leave their plastic bags. While the students worked on producing all this material, we kept in constant touch with Tomás Saraceno’s studio to ensure compliance with their communication guidelines. The workshop at the Cascine park was to be the cherry on the cake, and so to make sure we were properly prepared for it we held a test-assembly of the bags in accordance with instructions received. We set up a tight network of interlinked activities coordinated by the Education Department in close cooperation with a highly motivated group of IED teachers and students.

Communication project of Museo Aero Solar and bag collector on display at Palazzo Strozzi

The exhibition had only just opened and the first plastic bags had begun to appear in the containers when Palazzo Strozzi entered lockdown like so many other exhibition centres all around the world.

So, was it good-bye to Museo Aero Solar? Yes, but only in its physical format.

Team planning meetings got under way again and we developed a new strategy. We thought it would be interesting to transform this new sense of belonging into an on-line project tailored to reflect the “age of social distancing”. In the same way as Palazzo Strozzi’s visitors would have contributed with their plastic bags to the formation of a community, each one could now make his or her contribution to the project with a thought or an image through this website page.

It all kicked off with this: What ideas do we have for the future? Let’s collect thoughts, let’s talk about it and get them flying in a metaphorical sense. You have a different viewpoint from up high and so it allows to find new solutions for our way of life.

The project was brought to life thanks to our collaboration with IED Firenze, the unflagging work of Alessandra Foschi who coordinates the Advertising Communication course, Cecilia Chiarantini who coordinates the Interior Design course, the precious advice and experience of lecturers Marco Innocenti, Luca Parenti and Francesco Toselli and a tremendous working team comprising their students Edoardo Bartoli, Fiamma Batini, Damiano Boragine, Sara Cabrini, Livia Ceccarelli, Lorenzo D’ Elia, Camilla Giachi, Serena Grazia, Eva Lazzeri, Davide Lichen Lu, Mariasole Monaci, Pietro Niccolini, Liliana Parlato, Alessio Pezzi, Davide Pisoni, Lisa Purini, Martina Oliva, Zössmayr Sebastian, Irene Spalletti, Taeko Shinjo, Eulalia Talamo, Luca Varricchio and Carlotta Zandon.